March 26, 2023

Texts:

Psalm 130

John 11:21-44

I know this is going to surprise many of you, but I want to start with a poem. The poem is written by Willie James Jennings, a poet and teacher whom I love. This poem is entitled, “Quilters,” after the women who came before us, who loved with their hands, who preserved what was deemed trivial.

Quilters

They sat in the ancient place

of the broken and bombed,

the torn and taken, the loss and lost

remembering

the shattering

pockets and bags filled

with remnants captured

by keen sight

able to touch what be not

as though it were

possible to make.

These multi-shaded women knew

their anointing,

the power to join

broken glass, torn hearts, pebbles large and small, bloodstained brick, pieces of

those aprons that smelled like fresh bread, flashes of sadness caught in song, the

extra fabric from the wedding dress, little napkins, quick melancholies,

bunches of laughter, shreds from curtains from soul windows.

Then with eyes aligned,

stepping out onto nothingness,

handling things that could

slice flesh, and pierce skin

they placed pieces side by side

unprecedented, but now

colors and shapes dancing

intricate new steps making

visible pulsating joy

never before imagined.

Then they decided in majestic wisdom to create soft shelter

against the cold, against threat, against forgetting caress,

and as the final threads joined, they saw what God wanted

to call good, but could not create.

***

What a provocative final line! The women saw what God wanted to call good, but could not create. For me, this final line points towards that miraculous truth that is wrapped up in the name of our church, 8th Day. God wants to create and God longs to create with us, in and through the ordinary elements of our lives.

The poem speaks of remnants, shreds, pieces.

What Dr Jennings calls fragments.

***

My grandmother, my mother’s mother, Carol, is a quilter. When I had been dating Crisely for a while, my grandma offered to make us a quilt. She asked if it would be better to have a double-size quilt or a queen-size quilt. Not really picking up the hint that she was implying, I told her that I thought the double would be fine. Crisely looked at me side-eyed and suggested, wisely, that I call my grandmother back and change my answer.

Here is another quilt, made in part with old scraps of my mothers’ dresses. She made it for me and for my mother when I was born. When Crisely was almost due to give birth to Santiago, my mom took it down and sent it to us.

The blanket is one of the fragments of love that has been with me my whole life. It’s a fragment that reflects God’s goodness, God’s steadfast love over time. This quilt is perhaps part of the reason I am drawn to the poem in which

the multi-shaded women

decide in majestic wisdom to create soft shelter

against the cold, against threat, against forgetting caress..

***

In January, our family went to Peru in search of fragments, connecting family to family, generation to generation.

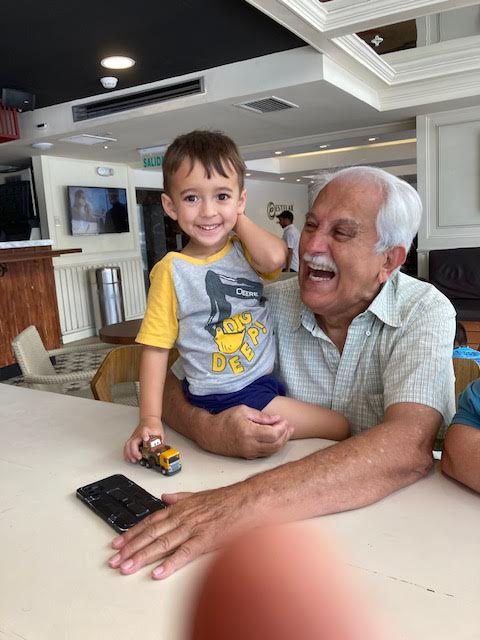

Tío Germán]

One of the parts of the trip I was most excited for was taking a small trip to the port town where my grandfather was born, off the Southern coast of Peru, three hours south of Lima in a city called Pisco. The trip was shorter than I had hoped; when you travel with lots of extended family, you have to tend to lots of needs and desires, and in the end we only had about 45 minutes in Pisco. We were unable to identify the home where my grandfather lived, nor were we able to meet or find anyone that lived in Pisco that remembered any of the Sasieta family. I left the city with a sense of ambiguous loss, a sense that more fragments could have been discovered but were now lost to history.

But I was wrong. When we got back to Lima, later in the trip, I was able to visit my great aunt, tía Gladys, my grandfather’s youngest sister. I had not seen her since I was a small child, so really, it was like meeting her for the first time. She is ninety years old and I did not know what to expect, what she would remember, how lucid she would or would not be. Fortunately, my tía is a firecracker of a woman, full of memory and story and wit. She is also an evangelical pastor, and so about an hour into our conversation, it felt right to ask if there was a Bible passage that was of particular importance to my great-grandmother, Antonina.

Without missing a beat, she said Psalm 130.

***

Out of the depths I cry to you, Yahweh!

2 O Lord, hear my voice!

These past few weeks, I have been wondering about the circumstances that drove my great-grandmother to confide in this Psalm and set parts of it to memory. My great-grandfather Luis was a journalist and died when a large roll of printer paper fell on him. My tía Gladys shared that she was just eighteen months old when her father died, and that my grandfather was three. My great-grandmother Antonina went from a relatively stable life as a housewife … to suddenly being a single mother of twelve children without an income. Gladys shared what papapa had shared when he was alive, that in those times, there was often not enough food. She shared about my grandfather contracting tuberculosis, about walking around Pisco without shoes, about being sent away to live with relatives because her mother did not have the financial means. When my papapa was twelve and when tía Gladys was ten, the family left Pisco and went to build a life in Lima.

Out of the depths, I cry to you, Yahweh!

O God, hear my voice!

Let your ears be attentive

to the voice of my pleas for mercy!…

3 If you, O LORD, should mark iniquities,

O Lord, who could gstand?

4 But with you there is forgiveness,

that you may be revered.

5 I wait for Yahweh, my soul waits,

and in his word I hope;

6 my soul waits for the Lord

more than watchmen for the morning,

more than watchmen for the morning.

My tía Joanna shared on this trip that my papapa’s whole sense of faith and personhood was built around his affection for his mother. When my grandfather was older and bedridden, I remember that he would sometimes attempt to recite a poem that he wrote for his mother. He could never quite finish it, but the fact that my grandfather always wanted to recite is important in and of itself. It was entitled “A La Madre” (To the Mother).

Being reminded of my bisabuela Antonina and the role that she had in my papapa’s life was a reminder that faith is a gift that we inherit, that we learn to hope in God by seeing others hope in God; like the psalmist, we watch the watchmen. We observe and mimic. We cry out to God because someone else showed us that we could. The love of God is something that is passed on by osmosis — by smell, memory and touch, by gestures, artifacts and stories.

By fragments.

***

***

The Psalmist cries out to God, and yet, within a matter of a few lines, she turns towards God’s goodness. This psalm is so spacious that we don’t know, really, if the psalmist has been injured or the one who has done the injuring. We don’t know if the psalmist needs to extend forgiveness or receive forgiveness. She begins verse four by saying, but with you there is forgiveness.

***

I think this is how we make the move that the Psalmist makes in Psalm 130. She starts in her own depths, in her own pain. But being reminded of God’s forgiveness and goodness, she senses her capacity to respond to that goodness, to wait for that goodness, to hope in that goodness and then, out of nowhere, to call her people to a similar posture.

By verse 7, she has moved in and through her pain. She has moved from prayer to community, from prayer to exhorting her people. Verses 7 and 8 read —

7 O Israel, hope in Yahweh!

For with Yahweh there is steadfast love,

and with him is plentiful redemption.

8 And he will redeem Israel

from all its iniquities.

***

The psalmist is suggesting redemption (or resurrection) is not some small, individualistic endeavor. She proclaims salvation for all of Israel. Redemption for its past and current sins. The psalmist reframes redemption as a generational work, something that God wants not only for us, but for the generations before us and the generations to come.

Perhaps the heart of Lent is remembering that we journey to the cross together. That resurrection is a communal and familial work. In our Gospel story, Lazarus is raised from the dead by Jesus … but Jesus is first moved by Martha. Jesus is moved by the community of Jewish people who surround and love Lazarus. Jesus completes resurrection, but he is first prodded towards it through Martha, Mary and the Jewish community of mourners, who in their own pray —

Out of the depths, I cry to you, Yahweh!

O God, hear my voice!

***

Since I began writing poetry, one of the poets I have been drawn towards is Lucille Clifton. Lucille Clifton published her first book of poems in 1969, when all six of her children were seven years old or younger. When asked about the challenges of writing poems as a mother, she quipped, “Why do you think my poems are so short?” .And yet, in so many of her poems, she chronicles and archives her family’s life, her people’s lives. She is a documentarian and a bridge between her forebears and her grandchildren.

Among the many award-winning books of poems that Lucille Clifton wrote, she also wrote one book of prose — a memoir entitled Generations, in which she puts together fragments of memory, both her own and that of her family, into a series of vignettes. The book is set during the funeral and wake of her father, which brings to mind the stories that her father would tell her, stories about people like her great-great grandmother Ca’line, a daughter of Dahomey women, who escaped slavery at the age of eight, walking from New Orleans to Virginia … stories about people like Lucille, her great-grandmother, after whom she was named, who was the first woman to be hanged in Virginia.

On the last page of her memoir, she writes,

I could tell you about things we been through, some awful ones, some wonderful, but I know that the things that make us are more than that, our lives are more than the days in them, our lives are our line and we go on. I type that and I swear I can see Ca’line standing in the green of Virginia, in the green of Afrika, and I swear she makes no sound but she nods her head and smiles.

Then she concludes with her family tree.

The generations of Caroline Donald born in Afrika in 1823

and Sam Louis Sale born in America in 1777 are

Lucille

who had a son named

Genie

who had a son named Samuel

who married

Thelma Moore and the blood became Magic and their

daughter is

Thelma Lucille

who married Fred Clifton and the blood became whole and

their children are

Sidney

Frederica

Gillian

Alexia four daughters and

Channing

Graham two sons,

and the line goes on.

***

Our lives are our line, and we go on.

Thich Nhat Hanh once said that when he meets a person, he meets their entire lineage.

I love this intuition that we bring our ancestors with us into community. Not only that, but that our ancestors prayed before us and show us how to pray.

Hundreds of years before Jesus, a psalmist

cried out to God from the depths.

***

As I consider the fragment and the inheritance that is this prayer, I am struck by the desperation of the psalmist. As a community, I think we have cultivated many spaces to hear one another’s desperate prayers when they arise. Carol, I think of your recent sermon when you voiced how afraid you were to lose Kent … and how God asked you if you would be willing to let him go. Steve, I think of your experience that you shared on the Road to Damascus retreat … and the overwhelming feeling that you were called to do more for racial justice. Luisely, I think of your discernment process a few years back, when you were considering moving to Washington State to practice midwifery and to do the thing that you love … and then, how sad you were at that idea of leaving us.

I honor the ways we hear each other’s deep prayers — in Ignatian Contemplation, with our open pulpit, in the intimacy of our small groups, in spiritual autobiographies, in our commitment to rest together, to grow together, to retreat together, to worship together.

And yet, how might we hear this prayer outside of 8th Day?

***

One final story.

A few years back, my grandmother shared with me a story about how grandmothers in Zimbabwe were helping their communities to treat depression. A Zimbabwean psychiatrist, Dixon Chibanda, one of just twelve psychiatrists in his country, wanted and needed resources, but all potential, financial resources were being directed towards child and maternal health and HIV-related illnesses. Though traditional mental health resources could not be provided, fourteen grandmothers stepped forward and offered their support to Chibanda’s work.

The grandmothers were not trained in mental health and their education experience was minimal. Rather than throw his hands in the air and give up this non-traditional workforce, he collaborated with these matriarchs. [According to a BBC article]

At first, he tried to adhere to the medical terminology developed in the West, using words like “depression” and “suicidal ideation.” But the grandmothers told him this wouldn’t work. In order to reach people, they insisted, they needed to communicate through culturally rooted concepts that people can identify with. They needed, in other words, to speak the language of their patients. So in addition to the formal training they received, they worked together to incorporate Shona concepts of opening up the mind, and uplifting and strengthening the spirit.”

One grandmother, Rudy Chinhoyi, who is seventy-two,

has spent ten years regularly meeting with HIV-positive individuals, drug addicts, people suffering from poverty and hunger, unhappy married couples, lonely older people and pregnant, unmarried young women…

After hearing the individual’s story, Chinhoyi guides her patient until he or she arrives at a solution on their own. Then, until their issue is completely resolved, she follows up with the person every few days.

Now, Rudy Chinhoyi is just one of 400 older women and grandmothers who are a part of what is known as The Friendship Bench — listening to young people, validating the fragments of their lives.

***

This world is a difficult place for young people.

The pandemic has sharpened this.

In 2021, one in five young people between sixteen and twenty-five are taking drugs to escape problems in their lives. Eating disorders have increased by 50% among the youth during the pandemic. And finally, according to one Harvard report, “61% of young adults and 51% of mothers with young children — feel “serious loneliness.”

I became a member of 8th Day because many elders in this community listened to me when I was in my depths. I remember being totally lost in my insecurities as a L’Arche assistant, doubled over outside the Starbucks, calling Kent Beduhn. I remember going for a walk with David Hilfiker in the woods, feeling rootless without a church. And once, after I prayed aloud in service about a hard interaction with another assistant, I remember Maria Barker approaching me in this backroom before one of our potlucks. She said to me, kindly, “It sounds like you’ve had a hard year.”

To all of you in the second half of life, to all you elders of this community, I want to say thank you. Thank you for bearing witness to my rough edges. Thank you for calling forth the gifts of those of us who are younger. Thank you for watching our kids and rubbing our feet. Thank you for encouraging us and challenging us to take risks.

And with that foundation, I also want to say this: our work is not complete.

As we accompany one another in our depths, let us also look out into the world. Let us be available for the future generations. Let us experiment with new structures that connect elders and young people. Let us be the multi-generational community that we are, weaving our fragments like quilters who know they have something to pass on.

And finally, let us be like Jesus, who in his listening, allowed himself to be moved to love.

Amen.

Bibliography:

https://www.christiancentury.org/article/poetry/quilters

https://www.vice.com/en/article/m7g5dq/young-people-taking-more-drugs-new-research